Patent Law’s Definiteness Requirement Has New Bite

The Supreme Court may have shaken up patent law quite a bit with its recent opinion in the Nautilus v. Biosig case (June 2, 2014).

At issue was patent law’s “definiteness” requirement, which is related to patent boundaries. As I (and others) have argued, uncertainty about patent boundaries (due to vague, broad and ambiguous claim language), and lack of notice as to the bounds of patent rights, is a major problem in patent law.

I will briefly explain patent law’s definiteness requirement, and then how the Supreme Court’s new definiteness standard may prove to be a significant change in patent law. In short – many patent claims – particularly those with vague or ambiguous language – may now be vulnerable to invalidity attacks following the Supreme Court’s new standard.

Patent Claims: Words Describing Inventions

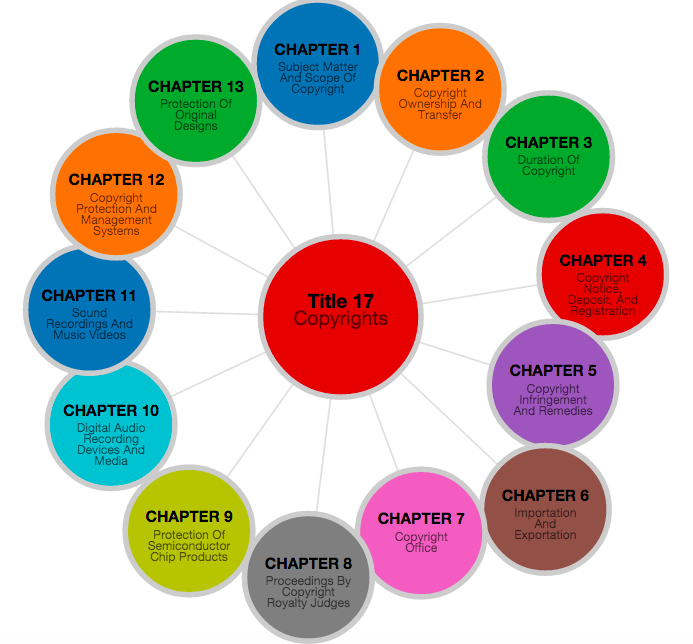

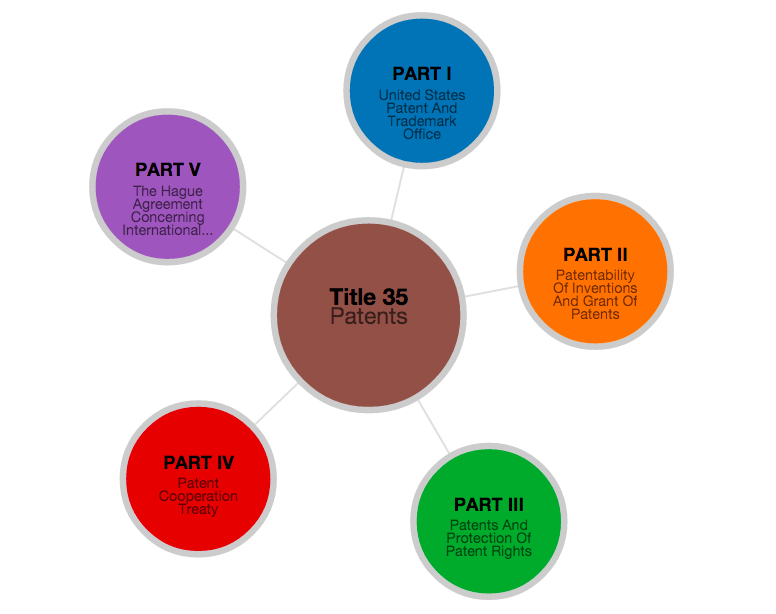

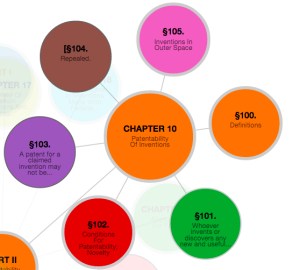

In order to understand “definiteness”, it’s important to start with some patent law basics. Patent law gives the patent holder exclusive rights over inventions – the right to prevent others from making, selling, or using a patented invention. How do we know what inventions are covered by a particular patent? They are described in the patent claims.

Notably, patent claims describe the inventions that they cover using (primarily) words.

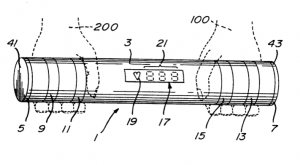

For instance, in the Supreme Court case at issue, the patent holder – Biosig – patented an invention – a heart-rate monitor. Their patent used the following claim language to delineate their invention :

I claim a heart rate monitor for use in association with exercise apparatus comprising…

a live electrode

and a first common electrode mounted on said first half

In spaced relationship with each other…”

So basically, the invention claimed was the kind of heart rate monitor that you might find on a treadmill. The portion of the claim above described one part of the overall invention – two electrodes separated by some amount of space. Presumably the exercising person holds on to these electrodes as she exercises, and the device reads the heart rate.

( Note: only a small part of the patent claim is shown – the actual claim is much longer)

Patent Infringement: Comparing Words to Physical Products

So what is the relationship between the words of a patent claim and patent infringement?

In a typical patent infringement lawsuit, the patent holder alleges that the defendant is making or selling some product or process (here a product) that is covered by the language of a patent claim (the “accused product”). To determine literal patent infringement, we compare the words of the patent claim to the defendant’s product, to see if the defendant’s product corresponds to what is delineated in the plaintiff’s patent claims.

For instance, in this case, Biosig alleged that Nautilus was selling a competing, infringing heart-rate monitor. Literal patent infringement would be determined by comparing the words of Biosig’s patent claim (e.g. “a heart rate monitor with a live electrode…”) to a physical object – the competing heart-rate monitor product that Nautilus was selling (e.g. does Nautilus’ heart rate monitor have a part that can be considered a “live electrode”)?

Literal patent infringement is determined by systematically marching through each element (or described part) in Biosig’s patent claim, and comparing it to Nautilus’s competing product. If Nautilus’ competing product has every one of the “elements” (or parts) listed in Biosig’s patent claim, then Nautilus’s product would literally infringe Biosig’s patent claim.

If patent infringement is found, a patent holder can receive damages or in some cases, use the power of the court to prevent the competitor from selling the product through an injunction.

Patent Claims – A Delicate Balance with Words

Writing patent claims involves a delicate balance. On the one hand, a patent claim must be written in broad enough language that such a patent claim will cover competitors’ future products.

Why? Well, imagine that Biosig had written their patent claim narrowly. This would mean that in place of the broad language actually used (e.g. “electrodes in a spaced relationship”), Biosig had instead described the particular characteristics of the heart-rate monitor product that Biosig sold. For instance, if Biosig’s heart-rate monitor product had two electrodes that were located exactly 4 inches apart, Biosig could have written their patent claim with language saying, “We claim a heart rate monitor with two electrodes exactly 4 inches apart” rather than the general language they actually used, the two electrodes separated by a “spaced relationship”

However, had Biosig written such a narrow patent, it might not be commercially valuable. Competing makers of heart rate monitors such as Nautilus could easily change their products to “invent around” the claim so as not to infringe. A competitor might be able to avoid literally infringing by creating a heart-rate monitor with electrodes that were 8 inches apart. For literal infringement purposes, a device with electrodes 8 inches apart would not literally infringe a patent that claims electrodes “exactly 4 inches apart.”

From a patent holder’s perspective, it is not ideal to write a patent claim too narrowly, because for a patent to be valuable, it has to be broad enough to cover the future products of your competitors in such a way that they can’t easily “invent around” and avoid infringement. A patent claim is only as valuable (trolls aside) as the products or processes that fall under the patent claim words. If you have a patent, but its claims do not cover any actual products or processes in the world because it is written too narrowly, it will not be commercially valuable.

Thus, general or abstract words (like “spaced relationship”) are often beneficial for patent holders, because they are often linguistically flexible enough to cover more variations of competitors’ future products.

Patent Uncertainty – Bad for Competitors (and the Public)

By contrast, general, broad, or abstract claim words are often not good for competitors (or the public generally). Patent claims delineate the boundaries or “metes-and-bounds” of patent legal rights Other firms would like to know where their competitors’ patent rights begin and end. This is so that they can estimate their risk of patent liability, know when to license, and in some cases, make products that avoid infringing their competitors’ patents.

However, when patent claim words are abstract, or highly uncertain, or have multiple plausible interpretations, firms cannot easily determine where their competitor’s patent rights end, and where they have the freedom to operate. This can create a zone of uncertainty around research and development generally in certain areas of invention, perhaps reducing overall inventive activity for the public.

Continue reading →