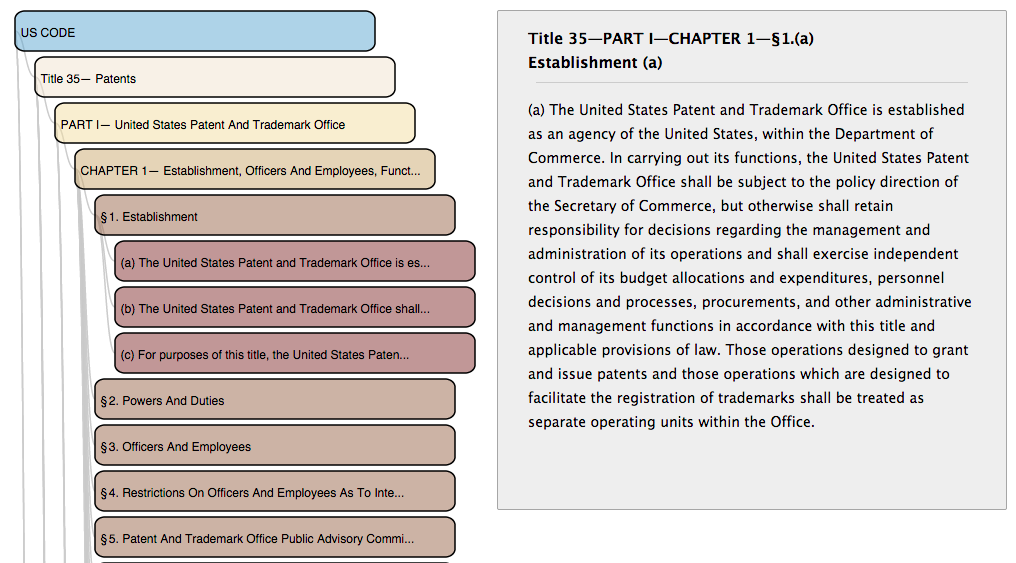

The explicit structuring of the U.S. law allows for increased computational analysis and visualization of the law, like this experimental demonstration app for navigating and visualizing the Titles of the U.S. Code that I recently created.

This post will discuss what it means for US law to be structured and why this enabled increased data analysis and visualization.

Structured Law and Computer Analysis

Around 2013, the U.S. government released the United States Code – in xml (extensible markup language) format. Releasing the laws in “.xml” means that the federal laws have now been given an explicit structure that can be read by computers.

To see why explicitly structuring the law in “machine-readable” form allows for more advanced computer analysis, let’s first examine the concept of explicit computer-readable structure and what this has to do with law.

The Structure of the United States Code

Most of the laws that the US Congress passes are collected in the US Code which is a large compilation of federal statutory law.

The US Code has a structure. At the highest structural level, the Federal Laws are divided into over 50 “Titles”.

Title 15 - Commerce and Trade .. Title 25 - Internal Revenue Code .. Title 35 - Patent Law

Loosely speaking, a “Title” corresponds to a different topical area for lawmaking. For instance, Title 35 contains most of the the Patent Laws, Title 20 contains many of the Education Laws. (Note that some Titles are a hodgepodge of unrelated topics housed under one document – e.g. Title 15 – Commerce and Trade, and the laws regulating some topics are found across multiple titles). However, the fact that laws are loosely placed by topic within Title is one form of overall structure.

Title Hierarchy: Parts -> Chapters -> Sections

Each Title, in turn, has its own structure and hierarchy. Every title is divided into smaller parts and sections in different levels. A typical structure of a title of the US code will have it divided into

Chapters, Sub-Chapters, Parts

Sections, Sub-Sections, Paragraphs

and so on. For instance, Title 35 – the Patent Code – has multiple patent laws located located in different parts of the overall hierarchy. Those laws related to the Patentability of Inventions in Chapter 10, etc.

Title 35 - Patents

Part 1 -United States Patent And Trademark Office

CHAPTER 1— Establishment, Officers And Employees

CHAPTER 2— Proceedings In The Patent And Trademark Office

§ 21. Filing Date And Day For Taking Action

....

Part 2 -Patentability Of Inventions And Grant Of Patents

...

CHAPTER 10— Patentability Of Inventions

§ 100. Definitions

§ 101. Inventions Patentable

Where is the law that tells us what types of inventions are patentable? That is located in Section 101 – “Inventions Patentable”. Within the overall hierarchy of Title 35, it’s located in Title 35 – Part 2 – Chapter 10 – Section 101.

Title 35

Part 2

Chapter 10

Section 101

And the text of section 101 is

SECTION §101 – Inventions patentable Whoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title.

Plain Text Law: Unstructured Text

The section just presented is an example of what might be called an “unstructured” (really “semi-structured”, but henceforth “plain text”) version of the law. A “plain text” version of the law means that the law as we normally see it written – in ordinary sentences designed for people to read (as opposed to computers).

I used the phrase “designed for people to read” to emphasize a point: such a plain text sentence may not be easy for computers to read. Computers are likely to find laws written in plain-text – like the one above – difficult to read. “Plain text” can be contrasted against “machine-readable” text, like the example below.

<section number="101"> <sectionText> Whoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter </sectionText> </section>

Computers prefer text to be rigidly structured and precisely labeled in this way. Such text is “structured” (and machine-readable) because a computer can, following rigid rules, methodically go through and unambiguously identify each part. In the example above, there is legal language within <sectionText>, and the computer knows exactly where the <sectionText> language begins and where it ends.

Plain Text Law: Implicit Structure

A typical law written as plain text does have a structure, but that structure is implicit. The structure includes what legal text goes with what section (i.e. do the words “Whoever invents a new..” go with Section 101 or Section 102), and the hierarchy (i.e. What parts are under what other parts – does Section 101 belong under Chapter 10 or Chapter 11). Let’s understand why the structure of a plain-text law is implicit and therefore difficult for computers to read.

TITLE 35 - PATENTS - Part II - Chapter 10 SECTION §101 - Inventions patentable Whoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title.

If you’re an attorney, you might be thinking, “There is an obvious structure in the law above – it is divided up into chapters, sections, etc. I can see that plainly.” If an attorney were to look at a printout of Title 35, she could see that it is divided into 5 “Parts”, each “Part” contains multiple “Chapters”, each “Chapter” in turn contains “Sections”, etc.) However, nothing in a printout of Title 35 that explicitly tells us about the hierarchy and organization of sections. There is nothing explicitly in the document that says, “A ‘Part’ is above a ‘Chapter’, and a ‘Chapter’ is above a ‘Section’.

Rather, that organization is implicit in the way the text is displayed and labeled given legal conventions. Attorneys learn to parse this hierarchy by relying upon common conventions about how law is labeled and structured, and general legal knowledge. Attorneys from training and experience – understand that in federal law there is a structure, and that “Chapters” come below “Parts” in the hierarchy, and that “Sections” are contained within “Chapters”.

Visual Cues and Implicit Structure of Law

In looking at the law, we also rely upon visual clues to show what portions are sub-parts of other portions. Often, when the law is printed, it is indented by several spaces each new level in order to make the hierarchy apparent, and sometimes emphasis like bold, etc, are used.

Additionally, we rely on visual cues to understand the different elements (e.g. headings vs. text of the law), and where one element begins and another ends. For instance, in looking at the above plain text printing of Title 101, we understand that the heading of the section is “Inventions Patentable”, and that the heading ends with the word “Patentable” where the bolded text ends. Thanks to bolding and spacing, we under that the text of the section begins with “Whoever invents…” The change in formatting and spacing indicates visually where the heading begins, and the content ends.

Unstructured Law: Difficult For Computers

The implicit structure in “plain text” sentences – like the law above – are obvious for people to see. However, to a computer, this implicit structure is typically difficult to unambiguously understand. A computer would not be able to understand (without accuracy issues) the same implicit cues (spacing, headings) that humans easily rely upon to separate out the law into its components and subcomponents.

In general, computers are not as good as people at understanding arbitrary visual cues – like Bold and spacing – that indicate the various parts. A computer might, for instance, not understand where the heading “Inventions Patentable” ends, and the content of the law “Whoever invents” begins. A computer might accidentally read the whole paragraph as one entity, “Inventions Patentable Whoever invents..”

While in principle you can program a computer to make educated guesses about the structure based upon the formatting and spacing, the computer is liable to make errors in “parsing” or reading the law and its structure if there are even minor changes.

In sum, when the law is printed as plain text – as it has traditionally been printed for hundreds of years – very basic computer tasks – such as separating out a Title into its different parts and sub-parts (e.g. Headings, content, chapters,etc), are be comparatively difficult to do with a high level of accuracy.

A simple task that merely involved reading the plain text law and counting the number of Sections in Title 35 – an easy task for a person — would risk errors in a computer.

US Code – Released as XML

In 2013, the U.S. House of Representatives released the titles of the U.S. Code as structured data in xml format. (Previously the Cornell Legal Information Institute had released an unofficial xml version of the federal law as well).

The fact that the law is now marked-up in .xml means that the Section 101 of the Patent Code now looks like this:

<section style="-uslm-lc:I80" id="id223e3b13-a7cf-11e4-a0e4-817d0c170cd7" identifier="/us/usc/t35/s101"> <num value="101">§ 101.</num> <heading> Inventions patentable</heading></p> <p style="font-size: 11pt;"><content> <p style="-uslm-lc:I11" class="indent0"> Whoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title. </p></p> <p style="font-size: 11pt;"></content> </section>

Computer Friendly Law

This version of the law is much less human-friendly to read, but much more computer friendly to read. Computers excel when there are precise, unambiguous rules to follow.

The .xml version of the U.S. Code makes the structure and hierarchy of the law explicit in a way that a computer can be told read. For instance, rather than guessing about where the text of section 101 begins ands ends based upon bolding and spacing, we have been told explicitly thanks to the <section> tags. The text of Section 101 is everything between the labels

<section> and </section>

The US Government took the time to label the exact start and end of every single section, part, etc of every law in the U.S. Code.

This means that a computer no longer has to approximate based upon visual cues or spacing to determine the start or end of the section. The end result is that a computer can unambiguously and accurately extract the text of any section, subsection, chapter, etc in any US Title.

Extracting the Hierarchy

Additionally, the hierarchy of parts within each US Title has been made explicit. For instance, Title 35 in .xml looks something like this:

<title><num value="35">Title 35—</num>

<part> <num value="II">PART II—</num>

<chapter><num value="2">CHAPTER 2—</num>

<section><num value="101">§ 101.</num>

</section>

</chapter>

</part>

</title>

This structure means that the computer does not have to guess about the hierarchy (e.g. what Part contains what Chapter) in the law based upon visual clues and indenting. Rather, “Title 35” explicitly contains Part I within its tags:

<Title 35>

<Part I>

<Part II>

<Chapter II>

<Part III>

<Part IV>

<Part V>

</Title>

Including Part I inside the Title tags <title></title> indicates that Part II is below “Title” in the law hierarchy. Similarly, Chapter 2

<chapter><num value="2">CHAPTER 2—</num>

has been explicitly been placed within Part 2’s opening and closing tags <part> </part>.

<part> <num value="II">PART II—</num>

This indicates that Part II is contained within Chapter 2, and so on. By explicitly placing one portion within the tags of the other portion, you are explicitly defining the hierarchy in a way that the computer can read.

The upshot is that computers can now precisely read or “parse” the structure (but not the meaning) of the U.S. code. Because of this, we can begin to create interesting visualizations and apps like the U.S. Code explorer that were not previously easy to in the era of “plain-text” law.

In a follow up post, I will explain more about parsing the U.S. Code in .xml and creating visualizations and apps based upon that